Was Government Really Better in Pitt's Day?

Originally published on Substack on November 06, 2025.

Please don't judge, but I occasionally read Dominic Cummings’ blog . Amongst his inane revolutionary natterings predicting the downfall of the very party he was once a senior figure in. He has a recurring argument that Britain would be far better governed without the permanent civil service it has today. He argues we should return to the days of Pitt the Younger, when Cabinet ministers held absolute sway over their portfolios and could hire/fire at will and leverage the seemingly endless patronage of the monarchy to overcome almost any institutional or political blocker to have their way. So I went off to read William Hague's Pitt the Younger biography and Roger Knight’s ‘Britain against Napoleon’ and well… I've thoughts……

-

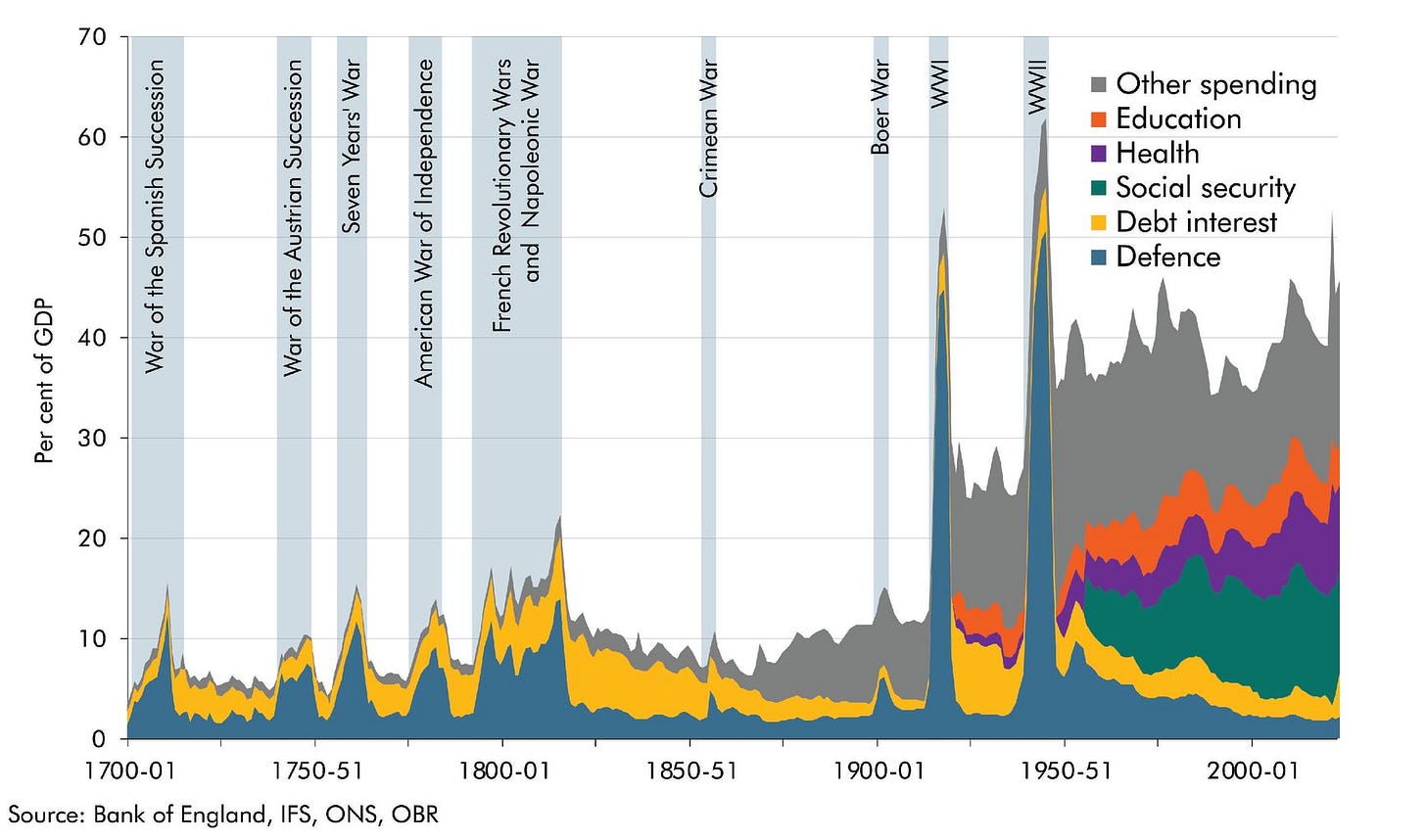

The role of government in the economy was miniscule compared to today

-

Radical reform of government is a lot easier when the a ten-ton weight is added to your side of the scales

-

For every vainglorious victory, Britain had numerous calamities even with "superstar” ministers. Effective parliamentary, administrative and legal boundaries matter.

Source: https://articles.obr.uk/300-years-of-uk-public-finance-data/

Source: https://articles.obr.uk/300-years-of-uk-public-finance-data/

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries the British Government was effectively just the equivalents of Ministry of Defence and the Foreign Office, with the Treasury to fund them. Sure there was a 'Home’ office but its role was effectively to use the armed forces to ensure peace at home, this being long before Peel's bobbies came on the scene.

Pitt spent almost the entirety of his governmental days deep in the detail of Naval procurement, Coalition negotiations and the financing or tax-raising to hold both together. A modern prime minister would find great joy in only ever focussing on one or two topics, compared to the gala of spinning plates that cannot be allowed to fall across health, social care, Environment, and everything else we have today.

Of course there is much less need of a large bureaucracy when the decision-making required on a day-to-day basis is one-tenth of what exists today and at that, was far simpler! That’s not to say that administrators of their (18th/19th century) day were not impressive. I can't imagine how the administration of the UK's first income taxes to fund the Napoleonic wars could possibly have worked without all the technology we have today.

Politics, What Politics?If you listen to the likes of Rory Stewart; the 18th and 19th centuries were a golden age of parliamentary grandeur, Pitt the Younger gained his premiership at the ridiculously young age of 24 largely because of his eloquence in the chamber. These were the days of high rhetoric and keen-edged dialectic, where speeches would go on into the small hours.

Impressive as I’m sure this sounds to an ex-player of the Oxford Union, the reality of whether many of those speeches actually mattered is completely different. Whilst the party system was only in its infancy making 'party management’ somewhat tricky, the reality was that the appointed Government of the day could be largely dictatorial in their actions if (and a big IF I know) they had the monarch onboard with their agenda. How you may ask?

Firstly: patronage. A dirty word today but in 18/19th-century terms it was just the cost of doing business. An earldom here, a sinecure there and very soon you can move almost any legislation through without too much fuss (assuming the crown agrees with you of course)

Next: elections. Pitt’s time was a loooonnngggg way from Universal Suffrage, but even ignoring this the government of the day had numerous means to sway the vote from safe 'government seats’ (imagine a permanent secretary deciding which MP to return), to Treasury 'funding’ of campaigns to the famous "rotten boroughs.”

Lastly: the Sovereign. Whilst todays cabinet ministers might technically 'serve at His Majesty’s pleasure’, those of the 18th century absolutely did. Imagine King Charles refusing to call an election or invite the opposition to take office because he didn't much like them and wanted to hold out until a scandal had blown over.

The reality was the opposition with certain exceptions largely didn't matter in terms of holding the government of the day to account and this is without even considering the role of the media. Sure there were embarrassments and screw-ups paraded through the chamber, but on the substantive decision making there was little that wouldn't go through.

A substantive and authoritative civil service is hardly needed if a government can rule by diktat without much fear of being held to account.

One Foot Forward, Two BackThe lack of effective opposition was key to why, for every chest-thumping victory from the Nile to Waterloo, Britain had a handful of failures.

From the 1793 Flanders campaign, to various foolhardy attempts to support French Royalists to crushing defeats of the first, second and (wait for it…) third Coalitions, we forget how hard a beating the French provided to Britain and its allies over the period.

It can definitely be argued that many of these disasters were just noise to the wider strategic successes of cutting France and her allies off from their overseas colonies, and funding continental powers to take on the majority of the grunt work across the fields of Germany, Italy, Austria and Russia but the point is that if an effective opposition had existed, no-way would the governments or ministers of the day have survived in post following many of them.

Whilst today’s ministers may yelp at the perceived restrictions put in place by 'the blob’ and fear of being called to account in the chamber, I'd much rather these were in place than allowing a jingoistic PM to waste lives and gold for no good reason (Oh wait, that did happ….. )

Even on the domestic front with all the benefits to hand, Governments of the day still failed to pass certain reforms primarily where the Sovereign disagreed with the policy aims. The ending of slavery was delayed decades primarily due to lobbying of the King by aristocrats with large holdings, similarly Ireland continued on its path to civil war due to the monarchy's intransigence on trusting Catholics in positions of power. As much as I tend to admire King Charles, I'm rather glad he doesn't have such influence on policy today.

On the Other HandI'll end with a simpler counter-argument to myself: whilst systematically or institutionally I don't think there is much from the time of Pitt we'd be happy living under today there is something to be said for the moral and intellectual quality of those in public life and at the top tables of government. In a world where there were far fewer opportunities for 'Type A’ personalities to compete, I think Parliament and many governments of the day were incredibly lucky to find and retain so many gifted politicians.

I somewhat doubt that today’s system of party lists and 'doing your time’ on the backbenches is conducive to attracting and retaining the same level of talent when there are many other opportunities for the talented and ambitious. That’s not to say I'd be particularly comforted to have a rash 25-year-old as Chancellor or PM but where I'll agree with Cummings is that the system actively dissuades many of our best and brightest from giving it a go.A really shame.

Lastly, I'll point out that in today’s terms the Pitt and his ministers earned salaries from £1-2 million for their efforts. Compensation that in material terms might attract those who would rather do something more with their lives than climb the greasy pole at Goldman Sachs.